Civil War in the East: 1862

Battle at Harpers Ferry Sep 1862

President George Washington established a Federal arsenal at the confluence of the Shenandoah and Potomac rivers in the small town of Harpers Ferry, Virginia. It also a had a railroad bridge for the Baltimore and Ohio railroad.

On September 15, 1862, a Union army 12,349 strong was stationed there. It was surrendered to Confederate General Stonewall Jackson.

Why would such a large force be surrendered after suffering only forty-four deaths and 173 wounded? To begin with, Col. Dixon Miles failed to establish control of the several hills which surrounded the town. Instead, he kept his force in the Harpers Ferry valley.

Col. Miles had spent the previous 38 years in the United States army. But after the Union lost the second battle at Bull Run, he was found by a military court to have been drunk while on duty. So, he was sent to the quiet town of Harpers Ferry a key Union military arms and supply center where it was thought he could do no harm.

General McClellan had wanted to incorporate this force into his Army of the Potomac. But, his superior General Halleck had denied his request. So there sat over 12,000 men in an indefensible position waiting to be captured.

Confederate general Robert E. Lee was willing to oblige. Besides, he wanted to invade Maryland and needed to capture Harpers Ferry in order to secure his rear. It wouldn’t hurt to capture all the arms and supplies stored at the Harpers Ferry arsenal, too. So he sent General Stonewall Jackson and his 23,000 men to capture the town and the arsenal.

Surprised that the heights surrounding the town were not fortified, Confederate forces took control. On September 15 they began a fierce bombardment of the town. Word that a relief force had been sent from General McClellan is said not to have reached Col. Miles. But records tell us that he told the officers of his command he thought surrender their best option. Miles was killed in the Confederate bombardment the same day of the surrender.

So the largest Union force of the Civil War would be surrendered after sustaining only 44 deaths and 173 wounded.

General Jackson would then rush his force to rejoin General Lee as the battle of Antietam had just begun.

The Gaining Control in the West

Gaining Control in the West

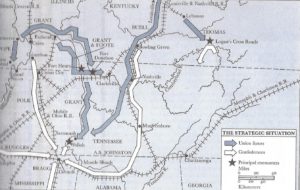

Corinth: Vertebrae of the Confederacy

After the stunning defeat at Shiloh, Confederate forces under Gen. Beauregard retreated to Corinth, Mississippi just ten miles south of Pittsburg landing (Shiloh).

Corinth was also called the ‘Crossroads of the Confederacy’. This was the strategic point at the junction of two vital railroad lines,

- The Mobile and Ohio Railroad and the Charleston Railroad.

- Both railroad lines penetrated the South as far as Mobile on the Gulf of Mexico, east to Charleston on the Atlantic Ocean and West to Memphis on the Mississippi.

Leroy Walker, the Confederate’s Secretary of War, called Corinth Mississippi, the ‘vertebrae of the Confederacy’.

After the battle at Shiloh was concluded, Union General Halleck said, “Richmond and Corinth are now the great strategic points of the war…”

So, after the battle of Shiloh was concluded, and Island #10 on the Mississippi was captured on April 7th, 1862, it was decided that Corinth was the next target for Union forces in the West. Toward that objective, General Halleck amassed three armies at Pittsburg Landing Tennessee,

1.Grant’s Army of the Tennessee

2.Buell’s Army of the Ohio

3.Pope’s Army of the Mississippi.

Before the end of April, Halleck had assembled almost 120,000 seasoned troops for the attack on the Corinth railroad center.

Corinth’s Defenses

Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard assembled nearly 68,000 men to defend the strategic rail center. But, after several weeks of siege by Halleck’s Union force, Beauregard saved his army from capture by slipping away on the night of May 30, 1862.

Other Mississippi River Battles

Meanwhile, A union flotilla under Flag Officer Charles henry Davis met and defeated a Confederate naval force at Fort Pillow. This was a Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi between Island #10 and Memphis.

On June 6th, Davis led his flotilla in an attack against a Confederate naval force of equal size. They met just north of Memphis. In just 90 minutes, the Davis force sunk seven of the eight Confederate boats while many Memphis residents watched from the city heights. The Union force gained a complete victory and secured the surrender of the city of Memphis.

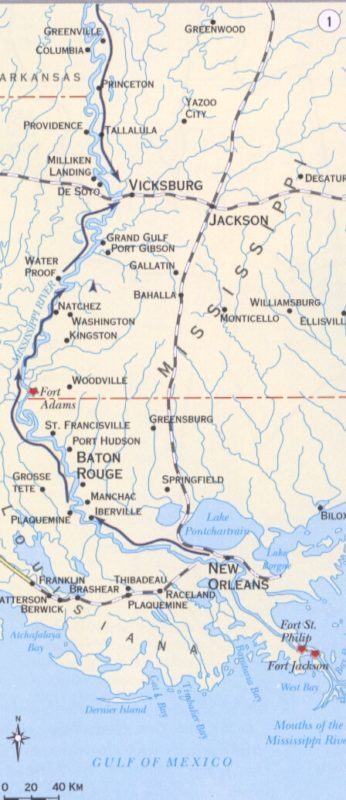

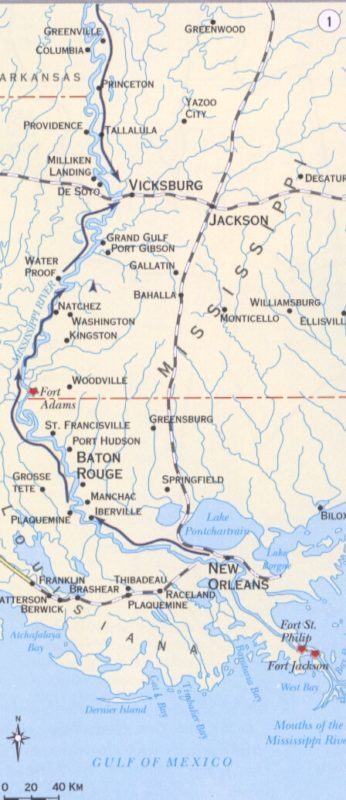

Union Effort to Control the Mississippi River By June 1862

The June 1862 victory at Memphis gave the Union control of the Mississippi River from,

1.Cairo, Illinois south to Vicksburg, Mississippi

2.From New Orleans, LA north to Vicksburg.

The way was now clear for the Union army to attack Chattanooga, Tennessee in the East and Vicksburg, Mississippi in the West.

The capture of Chattanooga, TE would open the South’s Hartland to invasion. The capture of Vicksburg would not only give the Union absolute control of the entire Mississippi River, but cut the Confederacy itself in half.

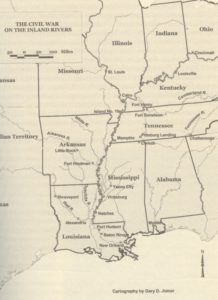

Farragut Moves North

Once New Orleans was securely in Union hands, Captain Farragut sailed his fleet north. He first target was the Mississippi River port city of Baton Rouge. The capital of Louisiana it was not prepared to repel an attack.

So, unprepared to defend itself, the authorities there surrendered the city to Farragut without a struggle. Once this was accomplished, Farragut moved his fleet to Natchez. The largest Mississippi River port city, it was the home of more cotton millionaires than any other city in South. It too surrendered without a shot being fired.

With the waters of the Mississippi River high, Farragut them moved further North to attack the second largest city in Mississippi, the river port of Vicksburg.

Lincoln had told his generals of Vicksburg,

“See what a land these fellows hold of which Vicksburg is the key. Here is the Red River which will supply the Confederacy with cattle and corn to feed their armies. There are the Arkansas and the White Rivers, which can supply cattle and hogs by the thousands. From Vicksburg these supplies can be distributed by rail all over the Confederacy.

“Let us get Vicksburg and all that country is ours. The war can never be brought to a close until that key is in our pocket.”

In April of 1862, at Vicksburg, Farragut’s order to surrender was refused. Held off by the guns on the heights of the city and fearful of becoming stranded should the river waters recede, Farragut withdrew his flotilla of ocean-going ships.

Capture of the city would be left to Grant and his land force. It would elude him for another fourteen months, until July of 1863.

Meanwhile, a large Union river force was gathering to attack Memphis, Tennessee, the last Confederate held port on the Mississippi River north of Vicksburg.

The Battle for New Orleans

The Battle for New Orleans

Following the success of Union forces on the Upper Mississippi, Washington’s attention focused on the gaining control of the Lower Mississippi. This was essential to the success of the Union strategy of splitting the Confederacy in half, to regain control of the southern part of the Mississippi River and it’s tributaries.

Toward that end, the city of New Orleans became the next major target. In 1860, the port of New Orleans was the second busiest port in the United States. Great amounts of cotton, sugar and grain flowed through that port on the way to world markets. In addition, in 1861, it was the largest city in the Confederate States of America.

Sixty year old Captain David Farragut was to be the fleet commander of the ocean-going vessels to be used in the attack on New Orleans. Assigned to him was a land force of 10,000 men under the command of General Butler.

The Confederate leaders thought the city was well defended. They were constructing two iron-clad ships there, blocking the river entrance with chains and sinking ships to further impede river traffic south of the city. The Confederates also had two forts guarding the entrance to the Mississippi at the Gulf of Mexico entrance: Forts Jackson and St. Phillip.

Poor planning and lack of financing slowed the progress on the iron-clads. So they were not ready when Farragut’s fleet arrived in late April of 1862. The river chains did not prove effective, either. Because under cover of darkness,e Farragut’s men cut them. As for the two forts, heavy bombardment using large mortars mounted on river barges, caused the soldiers manning the forts to surrender. Thus, the way was clear for Farragut’s ships to attack the city of New Orleans.

Writing after the battle, Admiral Farragut remembered the night time bombardment of the forts as “one of the most awful sights and events I ever saw or expect to experience… seemed as if all the artillery of heaven were playing upon the earth.”

Citizens of the New Orleans lined the entire water-front watching the battle and the on-coming Union fleet. They were furious with their leaders leaving them so defenseless and with the advancing Yankees. Not a shot was fired by Farragut’s men. And General Butler and his army of 10,000 soldiers occupied the city.

Aftermath of the First Battle of Bull Run

Aftermath of the First Battle of Bull Run

In April of 1861, after the Union lost Fort Sumter, the city of Washington was virtually undefended. So, too, Washington was again open to attack after the July 1861 loss at Manassas (Bull Run) to the Confederate army under General P.T. Beauregard.

The Union army was routed at Manassas. Thousands of survivors fled, leaving their equipment behind. There was no organized arm left to defend the Union capital of Washington City.

In April, President Lincoln said, he didn’t understand why General Beauregard hadn’t moved on Washington; neither did military commentators of the time. According to his critics, CSA President Davis was blamed for stopping his victorious army from capturing the Northern capital city.

Once again, in July of 1861, the city was in danger. After the loss at Bull Run (Manassas), the Union army was shattered. Having left most of its equipment on the battlefield, the army was also without organization or leadership.The Union’s political leadership was in panic mode as well.

In this atmosphere, President Lincoln called General George McClellan to Washington to rebuild the Union army. McClellan had become the only bright light in the wake of the Bull Run defeat. His Ohio volunteers had won a couple of military victories in the western region of Virginia (the future state of West Virginia). Thus, the media, hungry for a hero and good news, made him appear to be a miracle worker. They hailed him as the Union’s savior.

Upon arriving in Washington, McClellan wrote his wife that the situation was so bad in the Union capital, he believed he could become dictator if he chose.

Where was the Confederate army during all of this chaos in the North?

According to the Richmond press, Confederate leaders were sitting on their hands. General Beauregard, a Southern hero after capturing Fort Sumter and leading the victory at Bull Run, publicly criticized President Davis for this lack of action.

Beauregard pushed for following-up his victory at Bull Run with an attack on the North. He claimed that President Davis held the victorious Southern forces back, refusing to allow attacking and capturing Washington City. Instead, the CSA president wanted to fight a defensive war.

Thus, Washington City was spared a second time. And, McClellan was given time to rebuild and re-equip a Northern army.

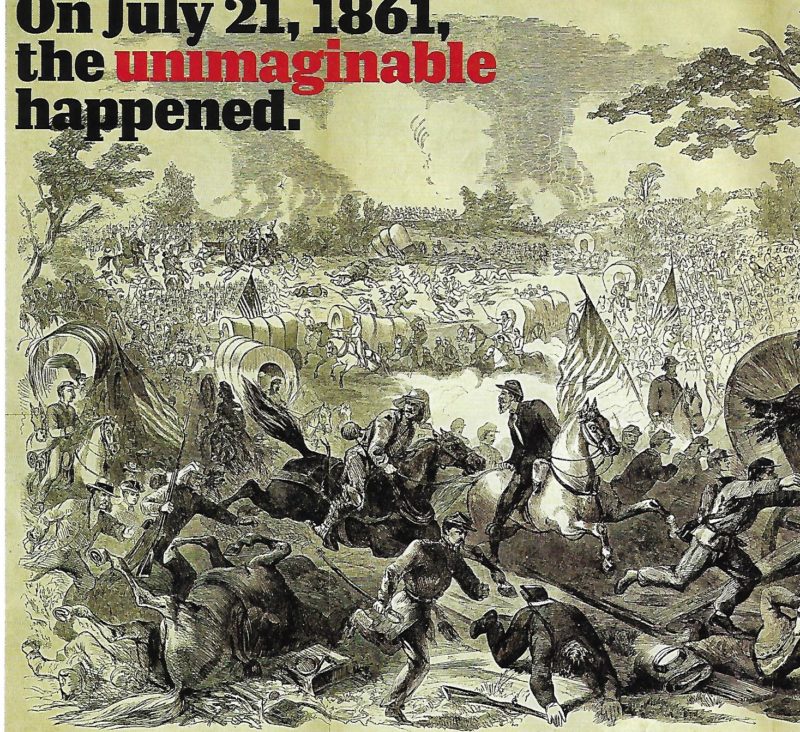

FIRST MAJOR BATTLE JULY 1861

First Battle of Bull Run July 21, 1861

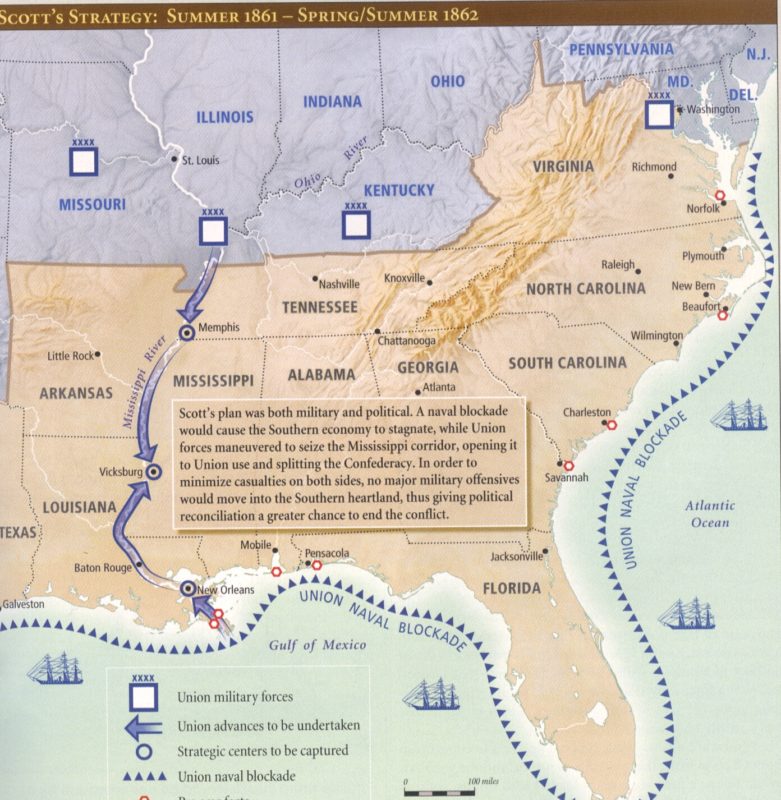

The 1861, war-plan devised by General Scott had wanted to avoid confronting the Confederate army on the battle field in the East. But, led by the press, northerners believed any war would be short lived. In reality, the public was led to believe that the Union army must only confront the Confederate forces in battle and the rebellion would be over. Thus, the press trumpeted, fighting could be ended quickly, with one or two battles. Just do it, Lincoln!

Instead, Scott’s plan called for a blockade. While that effort starved the Confederacy, he planned to first recover control of the Mississippi River and it’s tributaries. Thus divided, cut off from it’s traditional trading partners, and starved for supplies, the Confederacy would be likely to sue for peace. Such a war could then end without the tremendous property devastation and long casualty lists that could be requited to subjugate the Confederacy by war in the East. Such a war could also avoid creating a defeated and hostile Southern population in it’s aftermath.

It was not to be. The Northern press put great pressure on President Lincoln with it’s incessant, ‘On To Richmond’ demand. It was effective. Despite warnings from both General Scott and General MacDowell, that the northern forces were not yet ready, Lincoln’s cabinet persuaded the president to order an attack immediately with the objective of capturing the Confederate capital.

So, the newly formed Union army moved south to Manassas Junction, Virginia to confront the equally untested and somewhat larger Confederate army led by General P T. Beauregard’s Confederate Army of the Potomac. He would be joined by General Joe Johnston’s Army of the Shenandoah.

During a long day’s fighting, the verdict was in doubt, time and again. But late in the day, when fresh Confederate troops arrived by train from the West, the Union army’s right flank was turned. With no troop reserve of it’s own to stem the tide, the Union forces broke, and fled toward Washington City. It’s army completely broken, the first battle of Bull Run was a disaster for the North.

The next blog will focus on, Washington City: Undefended in The Aftermath of Bull Run

Trading With the Enemy

The Importance of Cotton in the North

In 1861, the South’s cotton was not only essential to the operation of New England,s mills, but also essential for the employment of tens of thousands of northern workers.

But an integral part of Union war strategy was to blockade the South’s ports. The blockade would deny the Confederate States of America the ability to export cotton and thus earn funds they needed to buy war material, and other goods they could not produce in their country. In addition, England needed cotton for it’s mills too. Southern cotton might just nudge them to recognize the Confederacy.

Thus, a dilemma. What to do about the need for the South’s cotton in New England as well as Great Britain ?

During July of 1861, Congress gave the president and the Treasury Secretary the right to issue, “such trading licenses as the public good might require.”

Very quickly, President Lincoln and his administration saw that they had virtually lost control of the situation. Cotton permits were sold on the streets of New York, soldiers were bribed, traders were blackmailed, and Treasury agents were quickly involved in the illegal cotton trade. The Secretary of War’s office reported that the thirst for cotton had corrupted and demoralized the army in the West, too.

General Sherman, with his headquarters in Memphis, complained that the sale of cotton north from the area under his command had resulted in the large supply of arms delivered to the Confederacy.

General Butler, arrived in New Orleans with a net worth of less than $250,000. He left a year later worth over one million dollars. A prominent Massachusetts abolitionist convinced Lincoln to liberalize between-the-lines cotton trading, saying “… we must have cotton.”

Butler was transferred from New Orleans to Norfolk. He just took his family members with him. There he set up his corrupt system. It was through his area that most of Lee’s supplies came until the end of the war.

Go to www.civilwrnovels.com to purchase books.

The War Changes

Early War Aim

As earlier revealed in a previous blog, the primary 1861 Union war Goal was to re-unite the country. Toward that end, the strategy was to hold off any large-scale destruction in the Eastern Theater, retake control of the Mississippi and its tributaries, and blockade the states of the Confederacy into submission. The CSA Goal was to maintain it’s independence from the Union by defending all its boarders.

So, any moves to emancipate slaves and otherwise destroy the property of citizens living in the ‘states in rebellion’ (Lincoln’s term) were discouraged. In fact, President Lincoln fired his Secretary of War Cameron for publicly advocating emancipation. He also forced General Fremont to rescind an emancipation proclamation he issued for the state of Missouri and then replaced him with General Halleck.

Lincoln said, “If I could end this conflict without freeing one slave, I would do it.”

Later War Aim

But, by mid 1862, the war still raged after 15 months of fighting.

In the West, the Union’s army under General Grant, General Pope, and Admiral Farragut won victory after victory. And the Union’s Brown River navy won control of the northern and southern Mississippi River and its tributaries. In fact, by mid 1862 only Vicksburg remained in Confederate hands.

In the East, the effects of the blockade were slow to materialize, several major battles were won by the Confederates and battle casualties were weakening support in the North for the war. So, that summer Congress passed the Second Confiscation Act. This allowed the Union army to seize or destroy any property believed to be useful to the Confederacy. Lincoln also floated a draft of his Emancipation Proclamation to be effective at he end of that same year.

General Grant, who had replaced Halleck commanding all Union forces, directed Gen. Sheridan to “Do all the damage to railroads and crops you can. (in the Shenandoah Valley) Carry off stock of all descriptions, and Negroes, so as to prevent further planting. If the war is to last another year, we want the Shenandoah Valley to remain a barren waste.” It is reported that Sheridan carried out Grant’s orders very effectively.

Further South, after his destructive march through Georgia to Savannah, General Sherman wrote to Grant about his intended invasion of South Carolina, “We are not only fighting hostile armies, but a hostile people, and must make old and young, rich and poor, feel the hard hand of war, as well as their organized armies.”

Thus, the war waged by the North against the Confederate States of American had turned ‘hard’.

The Road to Emancipation

The Road to Emancipation

At the Outset of the War:

From the outset of the war in April of 1861, Lincoln insisted his government’s only war aim was to re-unite the country. It was not, he insisted very publicly, to abolish slavery. He said:

“My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union and is not to either save or destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slaves, I would do it;, if I could save the Union by freeing all the slaves, I would do its; If I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would do it. “

Congressional View

Republicans in Congress thought otherwise .In 1862,

a. Thaddeus Stevens urged Lincoln to declare total war and make emancipation a war aim

b. March 1862, Congress forbade the army to return slaves to their masters.

c. April of 1862, Congress outlawed slavery in the District of Columbia June of 1862, Congress outlawed slavery in the western territories.

d. July 1862 Congress passed the 2nd Confiscation Act with provisions to free slaves of rebels.

Lincoln’s Response

Then, Lincoln backed a plan that would have compensated an owner in the Boarder States for each slave freed. He then intended to return the freed slaves to Africa. He pursued this policy because he feared inciting rebellion in the Boarder States and a negative reaction from Union soldiers who had joined the fight to save the Union, not free slaves.

But, by the end of 1861 he knew this initiative had failed. Slave owners in the Boarder States had not warmed to his purchase proposal, black leaders in the North opposed it too, and congressional leaders did not support it. His idea of shipping freed slaves back to Africa was not practical nor did it receive much support either. The issued of contraband slaves need to be addressed. And he was under great pressure from Congress and the press to do something about emancipation.

So, by mid summer of 1862, he then decided to issue an executive order freeing all slaves in states not controlled by the Union. This would make abolition a second war aim.

But he listened to Secretary of State Seward’s warning not to issue such an order out of weakness. Seward urged him to wait for a Union military victory to do so. Thus, he would issue the Emancipation Proclamation following the Union 1862 September military victory at Antietam Creek in Sharpsburg, MY.

A Second War Aim Jan. 1, 1863

Thus, President Lincoln announced a second war aim, that is an executive order ending slavery in the entire nation.

The Union won a victory at Antietam. om Se[ 17. 1862. Five days later, September 22nd, Lincoln issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. The final proclamation was issued on January 1, 1863. He said he used his power as Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy “as a necessary war measure” as the basis of the proclamation. He wrote to one of his generals,

“After the commencement of hostilities, I struggled nearly a year and a half to get along without touching the “institution”; and when finally I conditionally determined to touch it, I gave a hundred days notice of my purpose, to all the States and people, within which time they could have turned it wholly aside, by simply again becoming good citizens of the United States. They chose to disregard it, and i made the peremptory proclamation on what appeared to me to be a military necessity. And being made, it must stand.”

The text of the Emancipation Proclamation read:

“That on the first day of January in year of our Lord, one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State, or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free: and the executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no acts or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for the actual freedom.”

Lincoln’s executive order was never challenged in court. If effected slaves in ten states of the Confederacy. It did not effect slaves held in Maryland, Delaware, Arkansas, Missouri and Kentucky. Tennessee was mostly occupied by the Union and West Virginia was almost a state. So, it did not effect slaves held in those areas, either. Of the 4 million slaves, some 500,00 in the Boarder States were not freed. But some 20,000 were immediately freed in areas of North Carolina and the Barrier Islands of Georgia and South Carolina.

Another 300,000 slaves were not freed in Union controlled New Orleans and 13 Louisiana parishes. But the Proclamation did cleared up the issue of ‘contraband’ slaves, some 100,000; they were henceforth free.

As she Union armies advanced, the Proclamation provided the legal framework for freeing all slaves in the conquered areas. And, as seceding states rejoined the Union, it was required that thei new constitution of that state include the abolition of slavery.

Reaction

Many in the military initially found the Proclamation troubling; some even resigned their commission. But, by and large most soldiers recognized that taking away the South’s labor force hurt the Confederate economy and could very well hasten the end of the civil war.

Internationally, the Proclamation was warmly greeted. Some think it could have prevented help given the CSA from England and thus other European countries.

The obvious problem of what to do with 4 million former slaves after the conflict had ended was put off to another day. Union leaders had a war to win; Confederate leaders were fighting what increasingly appeared to be a losing fight for the survival of their infant nation.

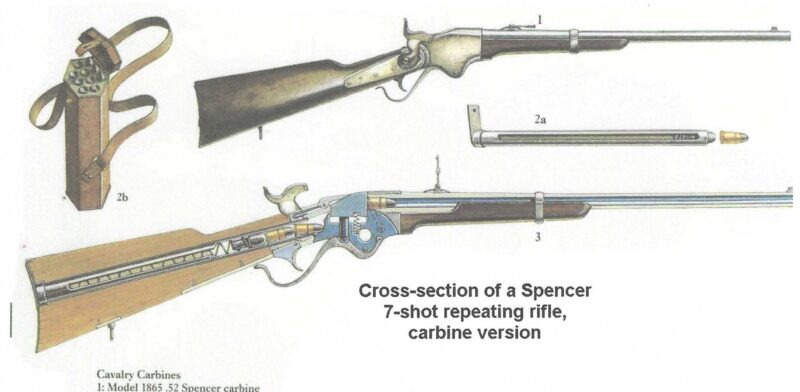

Civil War Arms: The Rifle

The Situation

It is estimated that over 720,000 military personnel died during the Civil War. Of those, 300,000 died due to combat wounds. Most of these deaths were inflicted by the combat rifle. Early in the war, most of the rifles used were: .58 caliber, muzzle-loading smooth bore rifles, using a Minni-bullet. The bullet & powder was encased in paper. Three rounds fired per minute constituted rapid fire, firing accurately for 50 to 100 yards. The traditional tactic was to fire a round and charge the enemy with bayonets. The hope was that you would cross the distance to the enemy line before those soldiers could reload.

Result:

Since ancient times many battles were decided by rushing ranks of closely-aligned men at one another. But since colonial times, the side which could fire fastest at a greater distance would usually win the battle.

Civil War Union’s Problem:

The Bureau of Ordinance headed by General James W. Ripley was responsible for approving the types of weapons purchased. This general favored smooth-bore, muzzle loading rifles to breech loaded weapons. He argued that his priority was keeping the waste of ammunition to a minimum and to assure reliability of fire. Over 1.5 million of the Springfield Muzzle loaders shown below were in use during the war, mostly by the Union.

Lincoln argued:

“But our people are not getting close enough to the enemy to do any good with them (muzzle loaders). We’ve got to get guns that carry further.”

Solution?

The Union introduced the rifled barrel which increased the range. But accuracy was a serious problem as was vision since smoke masked the target. Infantrymen frequently just aimed their rifle in the general direction of the charging enemy and fired. Rapidity of fire was still a problem: three rounds a minute was still the standard even though the range increased. Over 900,000 Enfield muzzle loading rifles shown here were used during the war, mostly by the CSA

Then, breech loaders were introduced which increased rapid firing. Smoke still obscured vision and accuracy.

The Repeating Rifle:

In 1862 Christopher Spencer produced a repeating rifle for demonstration. A soldier could fire seven times a minute without taking the rifle/carbine from his shoulder. And he could fire 250 rounds without stopping to clean the rifle barrel. Gideon Wells, Secretary of the Navy was so impressed with its accuracy, range, rapid and smokeless fire, he ordered 700 of them.

A 1862 demonstration for General McClellan’s staff resulted in a positive recommendation to the Bureau of Ordinance. But General Ripley refused to approve use of the rifle. At a battle near Chattanooga, TE in the fall of 1862, a regiment armed with Spencer repeaters repulsed a Confederate force five times its size. Ripley still refused to authorize buying the weapon.

Speaker of the House James Blair authorized the purchase of 10,000 Spencer repeaters and thus the Michigan Brigade was armed with them in the winter of 1862. Using them, they repulsed Stuart’s cavalry trying to attack the rear of the Union troops fighting off Picket’s charge. on day three of the battle at Gettysburg. That same August Sec. of the Navy Gideon convinced Lincoln to personally participate in a test of the Spencer repeating rifle.

Lincoln’s secretary wrote in his diary, “This evening and yesterday evening I spent with the president shooting Spencer’s new repeating rifle. A wonderful gun, loading with absolute contempt with simplicity and ease, with seven balls, and firing whole readily and deliberately in less than half a minute.”

Within two weeks, General Ripley was re-assigned by Lincoln and replaced by General Ramsay who said, “Spencer’s rifle is at the same time the cheapest, most durable and most efficient of any of these arms” He authorized the purchase of over 200,000 of them over the last two years of the war. He authorized the purchase of over 200,000 of them over the last two years of the war.

A Great Read! I couldn’t put this book down once I got started. The detail was great and I really like the main character, Michael. Knowing that so much research went into this book made it exciting to read!

A Great Read! I couldn’t put this book down once I got started. The detail was great and I really like the main character, Michael. Knowing that so much research went into this book made it exciting to read!