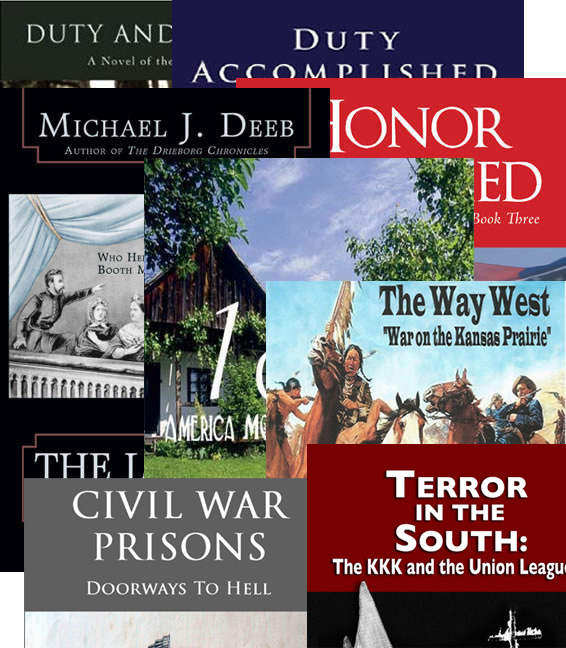

Civil War Prisons

I have finished writing a book in which Civil War prisons play an important role. Below is an early first read.

I hope you enjoy. I would love to hear your feedback. Please feel free to email me at civilwarnovels@gmail.com.

Prior to the outbreak of hostilities, there were no military prisons in the United States; maybe a small jailhouse on each military post. But neither the United States nor Confederate governments had established any large facilities.

When civil war came to the country very suddenly in April of 1861, virtually no preparations had been made by either side to prepare for war. It should not be surprising that no preparations had been made to care for prisoners of war either. The leaders on both sides predicted that the conflict would be over after a battle or two. Anyway, it was assumed that prisoners would be exchanged or paroled right after any battle that would be fought.

In April of 1861, Confederate Secretary of State Robert Toombs predicted that his country’s flag would soon fly over Faneuil Hall in Boston. That same month, Mrs. Davis sent out invitations to her friends in New York City inviting them to a tea she intended to hold soon at the Confederate White House in Washington City.

Following the fall of Fort Sumter, the Northern press trumpeted ‘On to Richmond’, promising their readers an easy victory on the battlefield and a quick end to the Rebellion.

None of this was destined to happen. On the contrary, four years of war followed Fort Sumter. During that time, over 674,000 prisoners were taken. At first, most prisoners were paroled right on the battlefield. But over 410,000 were not. Instead, they were kept in camps. These, some 150 compounds, could be found from as far north as Boston to the Dry Tortugas Island in the South; as far West as Fort Riley, Kansas and Fort Craig in New Mexico.

In these prisoner-of- war camps, over 56,000 men died during confinement amounting to 13 percent of the total prison population north and south. Since only 5 percent of men who remained on the battlefield died, it appeared your chance of survival was better fighting on battlefields than remaining in the relative safety of a prison.

Aside from the belief that the war would be a short one, there were other reasons the care of prisoners was not given a higher priority. The most important of which was that as with most wars, the governments involved had not prepared for a conflict. When it came, their energy and resources had to be devoted to organizing and equipping their fighting forces. Building fortifications and a navy as well as planning strategy took priority over the care of potential prisoners. Then, when it became apparent that the war would not be a short one, both governments’ energy was primarily devoted to maintaining their fighting force. Concern for prisoners of war remained a low priority.

To make matters worse for prisoners, in 1864, a decision was made by General Grant to end prisoner exchanges. He sacrificed the welfare of Union prisoners of war to keep Confederate captives in prison and away from returning to the battlefield after being exchanged.

The Outskirts of Washington City

“I think that be a Reb officer over there, lads,” Sgt. Riley told his squad of cavalrymen. “Let’s see how much trouble it’s gonna be ta’ get that horse off ‘en him.”

On patrol outside of the nation’s capital, Washington City, Sergeant Riley and his five man cavalry squad had been riding patrol southeast of the city. It was right after the first battle of Bull Run. Panic was still rampant in Washington for fear the Confederate army would follow its victory and be at the gates of the virtually defenseless city at any time. Riley’s mounted patrol was to provide the city with early warning of any attack.

On the other hand, the Confederates probed hoping to discover weaknesses in Washington’s defenses. Captain Pope had been leading his cavalry unit in that very effort when his horse stepped in a hole and rolled over falling on its rider. Shortly after, Riley’s squad came along.

“Keep a sharp eye out, lads,” he ordered. ‘This bird wasn’t out here alone ya’ know. I’ll look him over but you form a circle ‘round me and face out. I don’t want to spend this night tied up in a Reb camp, don’t ya know.”

While his men moved into the woods ten or so yards away, Riley approached the downed confederate officer with his weapon drawn.

“What have we here now?” he said. “Should we leave ya’ here now or take you with us. What’ll ya’ have laddie?”

“Tell ya’ what sergeant,” the trapped Reb officer responded. “Given the choice I vote that ya’ take me with ya’.”

It didn’t take long for two of Riley’s men to lift the horse enough for another Union trooper to pull the Confederate office free. He was lucky. The fall had not seriously injured him.

He was about five foot six inches tall, fair haired, blue-eyed, and one hundred fifty pounds or so in his polished riding boots. He looked like the typical cavalryman of his time.

“What now Sergeant?” He asked.

“Our troop commander will decide that,” Riley told him. “You’re headed for exchange or a prison camp be my guess. So, let’s get ya’ mounted now.”

“What did ya’ bring me this fine morning, Riley?” Captain Brennan said.

“We found this Reb pinned under his horse a few miles south a’ here, sir. Thought he might talk to another officer. He surely didn’t tell me much.”

“Thank you, Sergeant Riley,” Brennan told him. “You can leave the officer with me, Sergeant.”

“Yes, sir.” Riley came to attention, saluted and left his commanding officer’s tent.

“Well now,” Brennan began. “Have a seat, Captain. I’m having a cup of coffee. Can I pour you one?”

“Thank you. I would enjoy having a cup, Captain.”

While he was pouring the coffee, Brennan asked. “What name can I call you?”

“I’m Captain Richard Pope,” he answered. “I assume you are Captain Brennan?”

“You got that right, Reb,” Brennan snapped. “But, I didn’t catch the name of your unit, Captain Pope.”

“That’s because I didn’t give it to you, Captain Brennan.”

Smiling, Brennan said, “Of course, I forgot. But, you gotta know Captain, the more cooperative you are, the better your chance of being paroled instead of imprisoned.”

“Just how does a Yankee parole work?” Brennan was asked.

“Last I heard, you agree not to return to the fight until a Union soldier of equal rank is available to be exchanged for you. Is that how you understand it?”

“Yes, it is.”

“Are you a slaver, Captain?”

“Are you asking if I own slaves?”

“Yes.”

“No, I don’t own a single slave, Captain.”

“So, why are you in this fight?”

“To defend my freedom.”

“Freedom to own slaves?”

“If I decide to do that, yes,” Pope spat back. “According the constitution of my country, citizens have the right to buy, sell and possess property without the approval of some government official sticking his nose in my business. You might recall that even your Supreme Court affirmed that right for citizens of your country in the Dred Scott decision of 1856.”

“Oh my, I’ve got an educated Reb on my hands, do I?”

“Damn right Brennan,” Pope snapped.”

“According to the letters Riley found in your saddle-bag, you’re from Charleston, South Carolina. That’s the place where you traitorous Rebs started this war. Right?”

“I’m from Charleston, correct,” Pope affirmed. “That’s where you refused to leave our territory and forced us to throw you out.”

“That’s one way to look at it, I suppose.” Brennan responded.

“Reverse out situations,” Pope suggested. “You live in Charleston and see the flag of a foreign power flying over a fort in your harbor. I won’t take it down and leave. I refuse to accept a deal to pay for it either. Instead, I attempt to resupply the place indefinitely and even tell you when I’m going to resupply the troops stationed there.

“Just between you and I and the lamp post, wouldn’t that aggravate you all to hell” Pope asked.

“That surly would.” Brennan replied.

“Consider this” Pope continued. “ I appear to have made up my mind to hold on to the fort out in your harbor, at least that’s what I’ve said publicly several times. If you continue to allow me to resupply the place, occupy it and fly my flag, what does that say to your people and the world?”

“That I’m indecisive, maybe weak.” Brennan admitted.

“But you can’t allow that image to continue. At some point, don’t you have to insist that I leave and recognize your existence as a legitimate state? If not, don’t you have to give up the attempt at independence and come back into the Union?”

“This is all crap!” Brennan almost shouted. “You people fired upon the American flag!”

“Yes we did,” Pope admitted. “President Lincoln used your flag to taunt the South Carolina authorities and by extension the Confederate government. He put us in a box of sorts. If we let you stay at Fort Sumter and allowed you to fly your flag there we were admitting that we were not a sovereign state independent of the United States. If we didn’t, but forced you out we were Rebels firing on your sacred flag. We were damned if we did and damned if we didn’t.”

“So what? You started the fighting.”

“And Lincoln got his way whichever choice we made.” Pope concluded.

Brennan paused and finally responded. “I can see your point Reb. But I can’t get over the simple fact that you damned slavers fired on the flag of the United States of America.”

“I can’t deny that Yank. So, here we are, right?” Pope reminded him. “We’re at one another’s throat for sure. Is it all over a flag? I don’t think so. I believe it’s between two very different societies. We decided to recognize the difference and walk away and get out a’ your hair. You refused to allow that.

“You said it yourself, didn’t you?” Pope reminded Brennan. “I’m a slaver even though I don’t own a single one. You’re a Yank who represents a region that had become rich off cotton, sugar and tobacco and the slave labor which produces all of it.”

“Captain Pope,” Brennan interrupted. “I must admit that what you say has the ring of truth and common sense to it. But it’s all smoke in tha’ wind my friend. You and I are just little cogs in the great wheel of this thing.

“So drink up and I’ll take ya’ to my Regimental HQ where they’ll decide what ta’ do with yas.”

Pope stood, finished his coffee in one gulp, straightened his cap and jacket and said. “Thanks for the coffee and the stimulating conversation, Captain. I’m ready any time you are.”

A Great Read! I couldn’t put this book down once I got started. The detail was great and I really like the main character, Michael. Knowing that so much research went into this book made it exciting to read!

A Great Read! I couldn’t put this book down once I got started. The detail was great and I really like the main character, Michael. Knowing that so much research went into this book made it exciting to read!